This exhibition of works by architects and artists installed at Rudolph Schindler’s house in West Hollywood, California takes the fraught relationship between the architect and his wife as its theme.

The Soft Schindler exhibit features works by 14 architecture studios and artists that intend to add softness to or contrast with the house, which the celebrated modernist architect completed in 1922.

The showcase was curated by architecture critic Mimi Zeiger, who intends the project to explore the outdated idea of binary concepts.

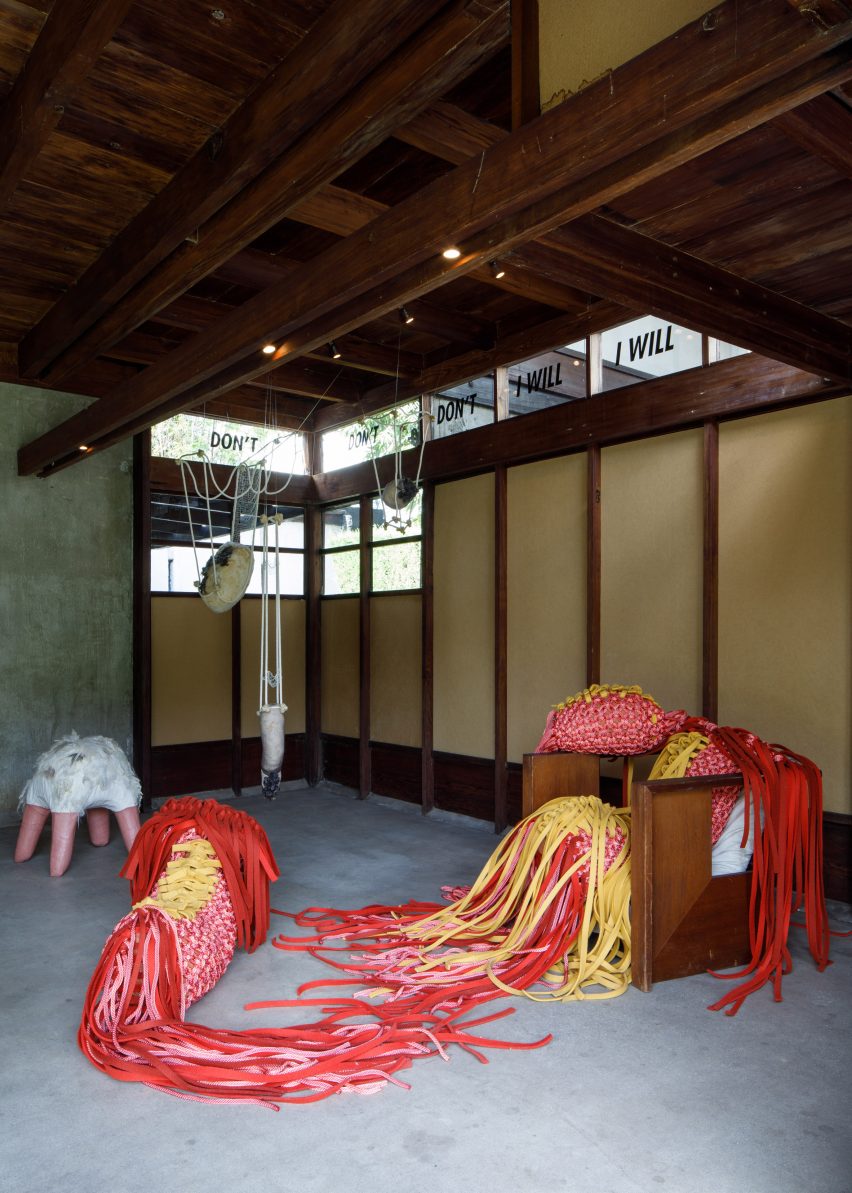

Among the works on show are the Swaddle Stools by Tanya Aguiñiga and Don’t! I will by Design, Bitches, which covers clerestory windows

“Soft Schindler participants, through their respective practices and presented works, show the incompleteness of binary ideas in architecture, sculpture, and design,” said a project description.

“Femininity versus masculinity, inside versus outside, heavy versus light, rational versus emotional – framing such notions as outmoded.”

Zeiger came up with the idea after learning about the relationship between Schindler and his wife Pauline, who lived together in the house.

The Austrian-born American architect had designed the property in West Hollywood as a home and office for two couples, with a shared kitchen. When tensions rose between Pauline and Rudolph, they chose to live in the separate wings.

Berlin artist Sonja Gerdes’s installation comprises bright colours that contrast the house’s existing materials

Pauline started to decorate her side, painting the walls pink and adding a 1970s-style shag rug, much to Schindler’s frustration, according to Zeiger.

“To RM Schindler, Pauline’s intolerable act violated a sanctum of modernism and his desire for honest expression of natural materials,” the project description continued. “But the exhibition aims to highlight that the home ‘has never been a binary’.”

Pauline Schindler’s alterations were not preserved when the house was restored to Rudolph’s specifications, something that the exhibition highlights.

“Archival photographs suggest material legacies in dialogue with Schindler’s rigorous geometries: tablecloths, pillows, curtains, flower pots – ephemeral elements that like the pink paint were not preserved when the residence was restored in the 1990s in approximation of the original intentions of the architect,” the team explained.

To showcase this, the exhibit presents work by 14 international artists and designers.

These include locally based Tanya Aguiñiga, Laurel Consuelo Broughton, Sonja Gerdes, Bettina Hubby, Alice Lang and Design, Bitches, as well as Leong Leong, Jorge Otero-Pailos and Bryony Roberts from New York.

Medellin’s Agenda Agencia de Arquitectura, Santiago’s Pedro Ignacio Alonso and Hugo Palmarola, and Barcelona’s Anna Puigjaner are also among the exhibitors.

Bettina Hubby’s humorous pillow creations are scattered on the floor

Zeiger chose the existing work of some of the artists and architects that responded to the theme of contrast.

“Alice Lang, whose ceramics use this kind of molten glaze on a series of male torso, really changes your understanding of what the body is, and surfaces,” she said.

Also included is the humorous work of artist Bettina Hubby: “I’ve seen some of the work that she’s done with pillows,” Zeiger added. “I was interested in what happens if we insert these kinds of projects in the house.”

AgendA Agencia de Arquitectura’s installation of died curtains references the cloths used to cover tables during dinner parties held by Schindler

Other works on show were designed for the exhibit to respond to the house itself.

Design, Bitches, for example, has installed a series of plexiglass panels with bold text onto expanses of glazing in the property.

They have phrases such as “Don’t” and “I will”, which reference the letters exchanged between Rudolph and Pauline during their period of separation.

These collages by Anna Puigjaner display floor plans with and without kitchens

The Kitchenless collages by Anna Puigjaner meanwhile form a continuation of the Spanish architecture’s work into kitchen-less cities.

Her research aims to promote the creation of communal cooking space in cities as opposed to private ones in homes – a particularly relevant notion in the design of The Schindler House, which has a shared kitchen.

“For her, this is a really a political move based on her ongoing research about collective kitchens becoming a way for people to come together to reverberate the kind of domestic duties of the kitchen,” said Zeiger. “Puigjaner really touches on a projection into the future.”

“When we look at it in the context of The Schindler House – which had a shared kitchen, as the one point that connects the two sides – that is an early start about appropriating the kitchen for different uses and new ways of using the space,” she continued.

Born in 1877, Schindler first started his career in Vienna, Austria, before moving to the US to work with 20th-century architect Frank Lloyd Wright, completing projects like Hollyhock House.

Other contributors include New York architecture sudio Leong Leong, which presented the Fermentation series

The Schindler House was originally designed to host the Schindlers and Clyde and Marian Chace, and is often referred to as The Schindler Chase.

Pauline left the property in 1927 and returned to live in the second apartment in the 1930s until her death in 1977.

In the interim, it was used by a number of different occupants including Schindler’s lifelong friend and architect Richard Neutra and art dealer and collector Galka Schey.

Today, the property is open to the public and managed by the MAK Center for Art and Architecture.

Soft Schindler is on show until 16 February 2020.

Photography is by Taiyo Watanabe.

Source: Rooms - dezeen.com